QE Is A Game-Changer: Economy Grows, Equity Markets Soar, Leaving The Fed Baffled

- Joe Carson

- Jul 2, 2023

- 4 min read

Policymakers must be baffled by the economy's and equity market's performances in the first half of 2023. Even after raising official rates to higher levels than initially expected, the economy outperformed their expectations, expanding by 2% in the first quarter and appearing to post a similar gain in Q2. On top of that, the S&P 500 index posted a 16% gain during the first half of the year, and the more speculative market indexes were up twice as much.

Forecasting errors are common, but policymakers' biggest mistake is the failure to properly assess the full impact of their traditional and non-traditional policy tools on the economy and finance. Conventional interest rate policy, even today, is not restrictive, but unconventional policy is the elephant in the room. QE is the game-changer as it floods the system with liquidity and keeps long-term rates from reflecting the changes in official rates.

Policymakers have raised official rates by 500 basis points since March 2022. That's a sizeable rate bump—the most significant increase since the early 1980s. But the starting point was also the lowest.

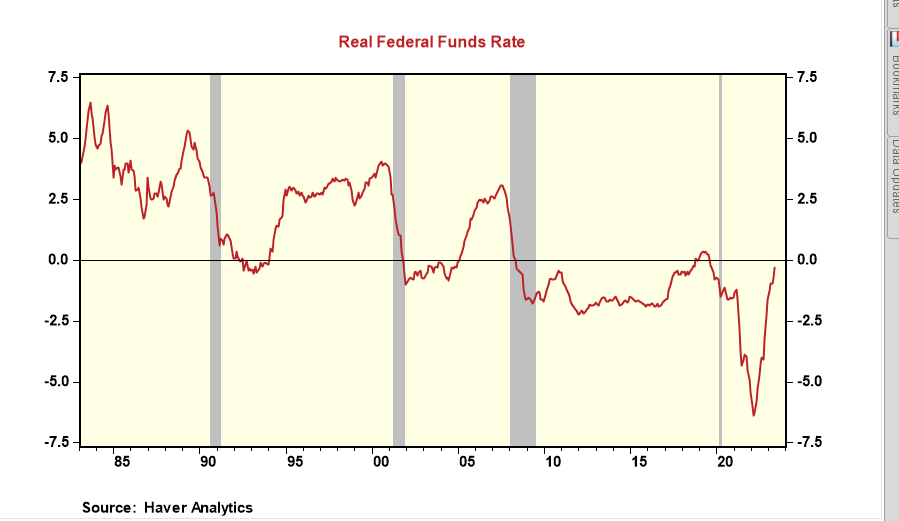

When policymakers started to raise official rates in early 2022, official rates were near zero, and core inflation was above 6%. That means real interests ( fed funds less core inflation) were negative 600 basis points, the lowest in the postwar period. Compare that starting point to the rate hiking cycles of the late 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s-- each one started with official rates above current inflation by 200 to 300 basis points.

Common sense would tell you that the lagged effects of the current tightening cycle would be markedly less adverse than the prior three cycles. Over the past 15 months, the stance of traditional monetary policy (i.e., the level of fed funds relative to inflation) moved from an overly accommodating position to one less so. Removing monetary accommodation, but slowly and steadily yet only partially, should result in slower growth. What happened? Slower growth. Should anyone be surprised?

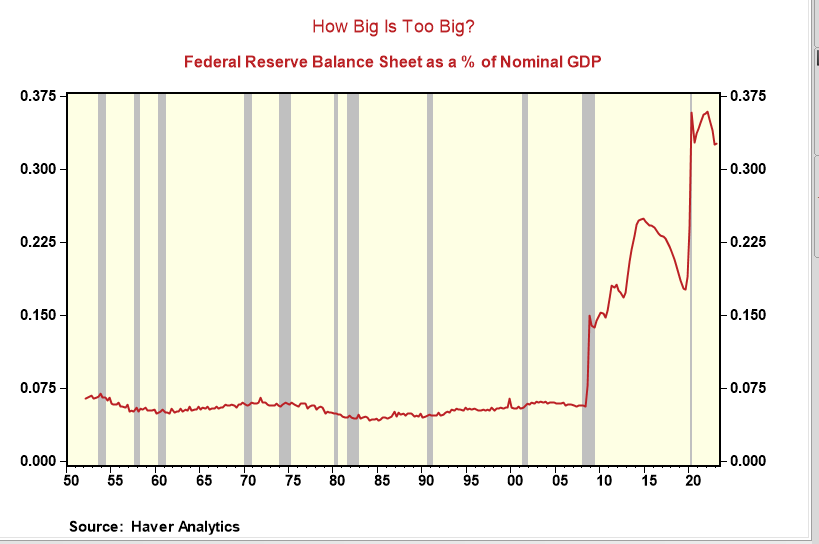

Nowadays, a complete monetary policy assessment must include its new tool, quantitative easing (QE). QE, or the direct purchase of government debt securities, was introduced after the Great Financial Crisis as an emergency monetary tool when the policy rates were zero, and policymakers felt the need to add liquidity to the economy. Policymakers never put a limit on the scale of QE, nor did Congress impose one. Has anyone at the Fed or Congress asked, "How Big Is Too Big?".

QE was to work primarily through the portfolio channel, as removing a large quantity of debt securities would force the private market sellers to replace them with other riskier assets. The direct effect of QE is to lift asset prices. That's happened. In the last three years, equity values on household balance sheets have equaled roughly 40% of total financial assets, and at one other time in history (the tech bubble), the share has been that high.

Can a policy that "inflates" financial assets be helpful to policymakers' general inflation fight? No, it has the opposite because the wealth effect creates an added layer of demand growth, inconsistent with the policy of high official rates to squash demand and quell inflation.

QE also has a strong and sustained impact on the shape of the yield curve, as it keeps long-term rates far lower than otherwise. That's important and often overlooked because for traditional monetary policy to be effective higher official rates must be transmitted up and down the yield curve. Yet, QE is blocking that natural rate-resetting process at the long end of the yield curve, resulting in an accommodative policy stance even as Fed Funds move higher.

The longer-run interest rates are the most critical for private spending decisions. The ongoing strength in housing construction is a case in point. A sizeable hike in official rates often brings about a significant correction in housing construction. Not this time. Why? QE has broken the link.

Assessing the effectiveness of a change in the stance of traditional monetary policy is difficult as there are factors that can affect it both ways. With unconventional monetary policy, the difficulty is magnified tenfold as there is only a small sample of data for evaluation and nothing in history that can come close to its current scale.

No one knows what level of official interest rates is needed to offset QE's stimulative forces because the Fed has never operated with an $8 trillion-plus balance sheet while attempting to quell inflation. The limited evidence indicates fed funds rate must be much higher than the current 5%. Policymakers are telegraphing two more rate hikes in 2023, and then that's it.

They are guessing like everyone else. Studies have shown that doubling the Fed's balance sheet from $4 trillion to $ 8 trillion was the equivalent of 200 to 300 basis points of official rate cuts. That might be how much more is needed to offset QE, and in doing so, it would put the real rate roughly equal to the level of past tightening cycles. Sometimes in finance, history repeats itself.

Comments