ISM's Prices Paid Indexes and Bank Credit Says the Fed Fight Against Inflation Is Far From Over

- Joe Carson

- Aug 3, 2022

- 2 min read

The monthly prices paid indexes of the manufacturing and service sectors from the Institute of Supply Management offer early insight into the underlying price trends in the distribution channels for the general economy. In July, the price paid indexes dropped for manufacturing and service industries, confirming the drop in spot prices for several commodities, especially oil. As a result, some have argued that inflation has peaked, and the Fed will be scaling back and ending its official rate increases before long. Both are wrong. Here's why.

Peak inflation is a meaningless statistic, as it provides no context to the reduction in speed or the duration of the inflation cycle. Moreover, the Fed is far from basing policy decisions on peak inflation; if they did, official rates would be far higher now.

Also, peak inflation implies inherent linearity to inflation, as what goes up often comes down. Prices tend to correct over time, but the correction process is uneven and flows through tighter monetary conditions and weakening demand. Official rates of 2.25/2.5% are too low to cool nominal private spending running at 10% and headline consumer inflation at 9%.

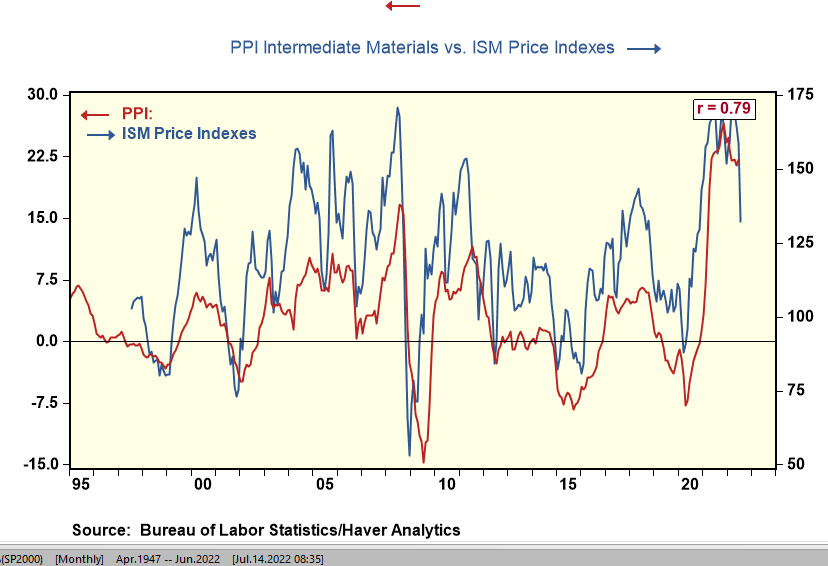

The ISM's prices paid indexes tend to correlate with changes in producer prices for intermediate materials and supplies. While encouraging, the sharp drop in the prices paid indexes still suggests double-digit year-on-year increases for materials and supplies.

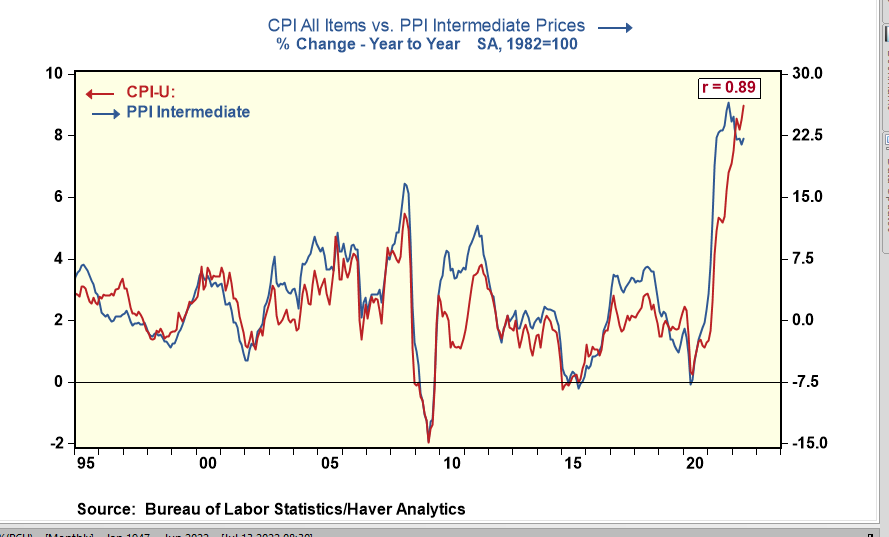

As long as prices for materials and supplies increase at a double-digit annual rate, the odds of a sharp, sustained slowdown in consumer price inflation are low, if not zero. Indeed, the correlation between PPI prices for materials and supplies and consumer prices is even higher than ISM prices paid by indexes and material costs (see chart).

Yet, added fuel to the notion that the inflation cycle will end quickly comes from, as some noted, broad money that has declined 1.3% annualized over the past three months. However, the group of inflation bulls fails to mention that bank credit over the past three months has increased 14% annualized, the fastest gain in three years. If higher interest rates do not lead to a slowing in credit growth, how does it slow the inflation process? It doesn't.

Recent comments by various members of the Federal Reserve indicate that they see the need to move official rates much higher before they can ensure inflation is moving lower on a sustained path. Price-paid indexes and bank credit figures agree with that assessment.

Comments