Fed's Goes Big & Late: Hard Landing Coming

- Joe Carson

- Jun 16, 2022

- 2 min read

Monetary policymakers are responsible for countering various "tailwinds" that have potential inflation consequences. But, policymakers are relying on inflation expectations to determine the appropriate stance of monetary policy when it should be the reverse. To be sure, people's inflation expectations flow from what they experience, so it's not a predictor of future inflation but an assessment of what is happening. So by waiting for inflation to appear in the data and surveys, policymakers have waited far too long, triggering the need for several rate increases with unavoidable adverse economic and financial consequences.

During the press conference following the June 14-15 Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting Fed Chair Jerome Powell stated that the rise in consumer inflation expectations was a concern. So, instead of raising official rates by 50 basis points, which Powell more or less promised at the last FOMC meeting in May, policymakers went big, raising official rates by 75 basis points with the hope of squshing rising inflation expectations.

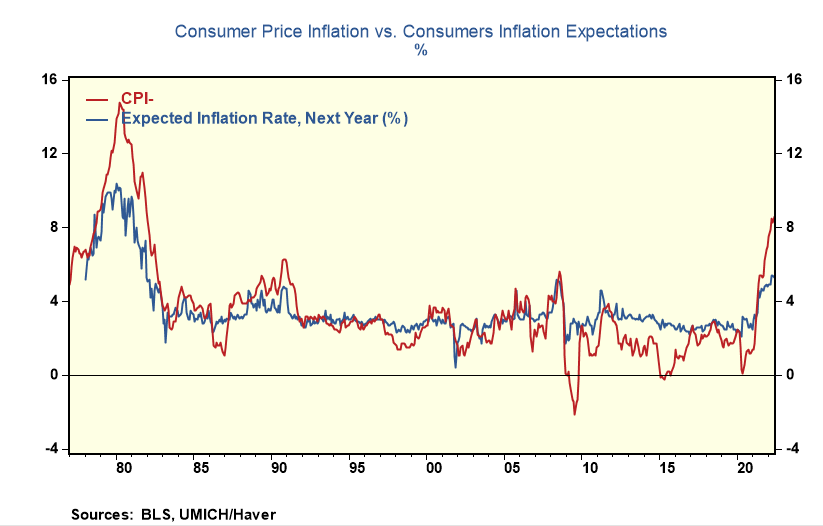

Policymakers think inflation expectations have a forward-looking character. The data do not support that view. The Univerity of Michigan consumer sentiment survey has recorded people's inflation expectations since the late 1970s. So there is a data record of how people's expectations of inflation reacted to actual high readings of inflation.

At the start of 1978, people expected one-year inflation of 6% when reported inflation was also 6%. Over the next several years, people's expectations increased to as high as 10%, as inflation zoomed as high as 15%. The 1970s survey data shows that inflation expectations change based on experienced or realized inflation. In other words, expectations are directional with actual inflation and do not predict what will happen.

Updated policy rate forecasts by FOMC members at the June meeting show an additional 150 basis points to 3.4% in official rates versus what was expected back in March. Policymakers now realize that they need to raise official rates by more than what occurred in 1994, and even then, it would be not enough to bring inflation back to the 2% mark—an additional 50 basis points of hiking in 2023.

The problem with monetary policy nowadays is it relies too much on telegraphing or communicating what it plans to do after it sees the data. A data-dependent policy, by definition, reacts late, triggering a more wrenching change in official rates than what would have occurred if policymakers acted preemptively. It is unrealistic to expect a good outcome given how far behind the Fed says it is today. Investors forewarned.

Comments