Equity Investors: All Bad News Is Not The Same, Nor Does All Bad News Trigger A Friendly Fed

- Joe Carson

- Aug 23, 2022

- 3 min read

Equity markets have a unique ability to look beyond the bad news and begin to think about the prospect of good news. Yet, all bad news is not the same, nor does all bad news trigger a friendly policy response by the Federal Reserve. Yet, equity investors still believe that bad news eventually leads to easy money.

This time is different because the source of the bad news is inflation, unlike the bad news of credit and liquidity crisis episodes that triggered a Fed response. Also, the Fed operates nowadays with a new inflation-averaging framework that constrains its policy flexibility when inflation is high.

Following the sharp plunge in equity prices during the onset of the Covid pandemic, the broad equity averages took only four months to recoup their losses as the Fed flooded the markets with liquidity. It took a few years to recoup the losses following the Great Financial Recession. Still, before the equity market rebound and recovery ended in 2019, equity prices were 2X the prior cyclical peak as the policymakers maintained a zero official rate policy for seven consecutive years and a low-interest rate policy for the next four.

Bad news nowadays is on the inflation front, something equity investors and policymakers have not encountered in several decades and is fundamentally different from the credit and liquidity issues of the Great Financial Recession and the non-economic causes that triggered the pandemic crash.

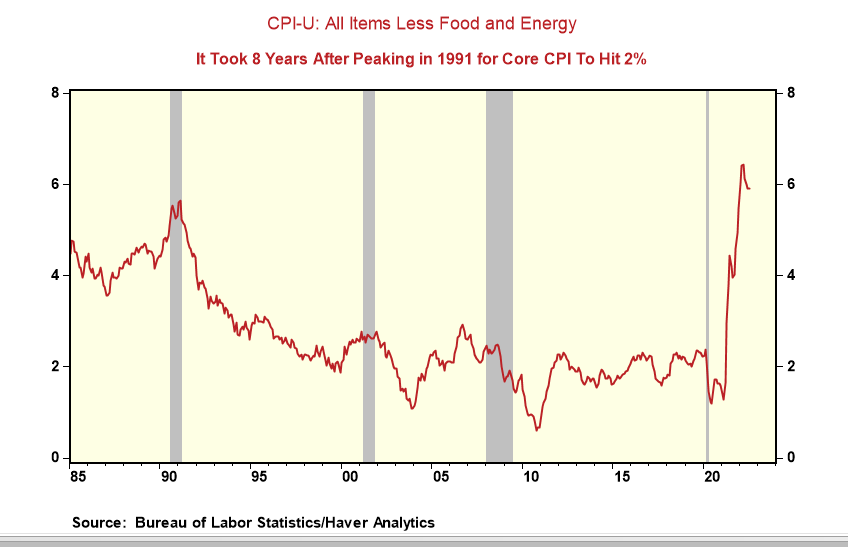

Core inflation is running at a 6% annualized pace. The last time the US faced a similar core inflation problem was in the early 1990s, when core inflation hit a peak of 5.6%.

The Fed did not have an explicit inflation target back then like today. Still, the Fed attempted to keep a lid on cyclical inflation, ensuring it did not return to peak levels, hiking official rates when pipeline pressures surfaced and lessening official rates when commodity and input costs subsided.

Yet, it wasn't until 1999, eight years following the peak did core inflation slow to a low 2% rate, today's inflation target of the Fed. During most of those eight years, the Fed kept the nominal federal funds rate far above core inflation, unlike today, where it stands far below. Given the exceptionally tight labor market and rising labor costs, it would take a very restrictive monetary policy stance in place for an extended period to produce a similar result in core inflation nowadays.

History says equity investors must confront a new reality:

Bad news on core inflation doesn't disappear quickly. It might not take eight years to hit a 2% target, but equity investors face a new reality even if it is half as long.

The Fed's inflation target of 2%, 400 basis points below the current core inflation rate, dramatically reduces the chances of a pivot (shifting from tightening to easing) in monetary policy anytime soon.

The Fed's new inflation-targeting framework, adopted in 2020 and overlooked by many, significantly reduces the odds of an easier policy stance even if core inflation slows faster than may expect. That's because high inflation readings in 2021, 2022, and possibly 2023 mean core inflation would have to run well below 2% for several consecutive years for the Fed to stay "true" to its average inflation commitment.

The message to equity investors is straightforward: the Fed responds differently to high inflation data than it does to credit and liquidity crises. Reducing equity exposure and risk makes sense until the Fed instills a more restrictive policy to contain core inflation. That's because bear markets plagued by inflation and a misaligned monetary policy (e.g., the 1970s) run long.

Comments