Asset Inflation Cycles: Modern-Day Form of Inflation

- Joe Carson

- Feb 2, 2024

- 4 min read

In the last twenty-five years, asset price cycles have become more dominant in business cycle analysis, and in doing so, asset inflation cycles have become the modern-day form of inflation. Their importance has become so critical that they have become an explicit part of monetary policy via its new tool, quantitative purchases, whose primary purpose is to increase asset prices/values. With the Federal Reserve now a key player, do asset price cycles still exhibit similar boom and bust patterns as was the case in the past? Or can monetary policy permanently elevate asset prices above and beyond economic and financial fundamentals?

Asset Price Cycles

Several theories help to explain why asset price cycles have become more significant and more volatile over the past twenty-five years.

First, monetary policymakers changed its operating framework in the mid-to-late 1990s, just before the asset price tech bubble. Policymakers abandoned the money supply and credit anchors and started to track real official interest (i.e., Fed Funds level less consumer price index). That created an informal price-targeting policy regime, which years later became formal and removed a policy framework that responded to financial conditions and imbalances that could trigger future inflation or economic problems. Ever since the change in its framework, policymakers have refused to use official rates to dampen speculative and significant asset price cycles.

Second, in the late 1990s, BLS removed the house price signal (i.e., it stopped surveying owner homes for the rent calculation) from its measure of consumer price inflation. That change further broke the link between real estate and consumer price inflation and changed the correlation between real estate and equity prices to positive from negative. So, real and financial asset price cycles became mutually inclusive, which was the opposite of what was usually the case in previous cycles.

Third, globalization (i.e., the ability to import cheap goods) played a role in the US inflation cycle as it helped dampen goods price inflation. With monetary policy shifted exclusively to reported inflation and less to financial conditions, tame consumer price inflation contributed to investors speculating, and often winning that monetary policy will remain easy regardless of asset inflation.

Asset price cycles do not generate public outcry as general inflation cycles, even though history shows they can be equally destructive and destabilizing. That could be because asset price upswings can generate substantial wealth gains while general inflation penalizes everyone. Yet, policymakers have a mandate for financial stability, so they must stand up against the crowd even if it's politically unpopular.

Asset price imbalances or bubbles are hard to detect in real-time and can last long. Yet, one can gain perspective by comparing current market valuations of real and financial assets to past periods of boom and bust.

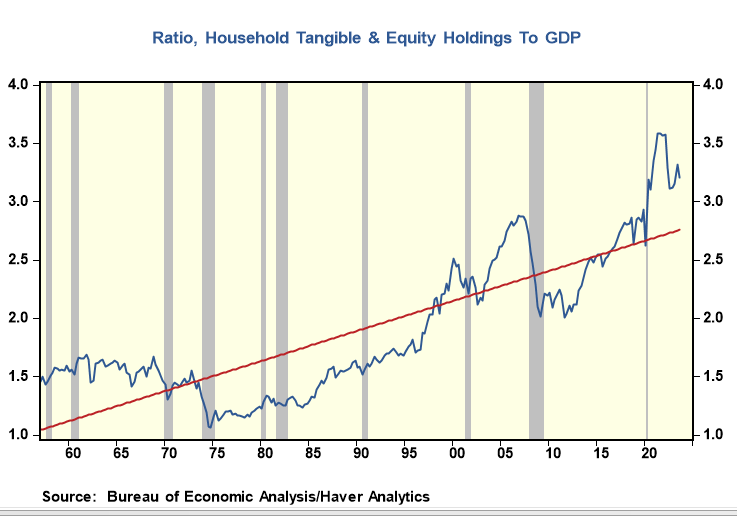

During the tech bubble, the market value of the real estate and equities on household balance sheets to nominal GDP spiked to a record 2.5 times, falling back to below two during the bust (see chart). The housing bubble helped fuel a more significant spike in market valuations to roughly three times GDP, and again, history repeated itself, as it often does in finance, with market valuation falling back to below two.

The Fed's QE 1 program helped asset prices recover ground lost during the Great Financial Recession, and QE 2 has pushed asset values to GDP to a new record high. Based on Q4 changes in asset prices and GDP, the ratio is estimated at 3.5, just shy of the record high at the end of 2021. If history were to repeat itself, it would take a 35% to 40% decline in both real estate and equity values to match the fall in the Asset/GDP ratio following the tech and housing bubbles. That is not a forecast but an illustration of how far current valuation have deviated from trend. Liquid assets correct sooner and more sharply than real assets so the equity and real estate declines, if they do occur, would not be proportional.

Can monetary policy permanently increase the nominal values of real and financial assets with its new policy tool (QE)? Monetary policy can make things look better and last longer, and QE has done that. But to permanently increase the earnings power and asset valuations is not something monetary policy can do. Every excessive asset and non-asset price cycle in history eventually broke for one reason or another. The current cycle should be no different.

Policymakers are debating when to reduce official rates because general inflation has slowed. Reducing official rates would be a significant policy mistake because of the price imbalance in the asset markets. Instead, policymakers should comprehensively review their policies because the economy's performance, evident with the strong job and wage gains in January, says the total stance of monetary policy remains too easy. In doing the review policymakers will learn that their new tool of quantitative purchases offsets a significant chunk of their official rate policy. In the current climate, it makes more sense to accelerate the reduction of the Fed's balance sheet than to lower official rates.

Comments